Strange Things Happen at Sea

Tony was excited about sailing round Lands End. His experiments with anti-sickness medication had allowed him to sail past Mousehole towards the open sea in moderate weather. He thought he had beaten the bugbear that confined him to shore fishing when many of his friends were proper seagoing fishermen. It was something he just had to try.

We waited for reasonable weather and prepared for the journey. I was nursing the boat back to Hayle to make good the storm damage. Newlyn Maid was more than seaworthy but I would be grateful for someone to take the helm occasionally. A second helmsman would be a relief from what would otherwise be at least 12-hours of tiring non-stop steering. The temporary bungy-cord self-steering was helpful but Tony might make the journey far easier. Also, his presence would mean I could make running repairs without worrying about the helm.

Our plan was to sail the boat around and only use the engine getting in and out of the harbours. It would mean a minimum journey time of 12-hours but more likely 24-hours. I told Tony that if the sea were too lumpy we would turn back before Lands End and return to Newlyn. If he did become sea-sick we would use the engine but it might still take from 6-hours to 12-hours to get to a harbour. There was enough fuel to make the whole journey by engine and we should only need to motor at most half that distance to reach a harbour. I reminded him we could only enter Hayle at high tide. Given the wind direction we might divert in an emergency to St Mary’s on the Isles of Scilly.

The next two days were weird.

Calm Sea?

The forecast was for a slight to moderate sea with a fairly strong wind. Preparing the boat on the Newlyn pontoons, we could hear the wind whistling in the rigging. Stronger than forecast but not a particular concern. Small fishing boats started to come into the harbour intermittently. One boat pulled up next to the Maid and the skipper called across.

“You’re not going out in that surely?”

“Why? Is something up? The forecast is for a slight sea.” Tony replied.

“Well, there’s nothing slight about it. I wouldn’t go out in that. Where you off?”

“Round the corner to Hayle,” Tony said with a proud smile.

“Rather you than me!”

Listening to this did not fill me with confidence. The fishermen might be teasing us as the forecast was good. I phoned the shore crew and asked them to check if the forecast had changed. No, the Meteorological Office and Passage Weather were still saying slight to moderate sea with a reasonably strong offshore wind when we round the corner. I asked them to check yet again and they confirmed everything was fine. I asked Tony if he still wanted to go.

“Hell yes,” he said.

A Penlee lifeboatman was passing and stopped for a chat. He asked when we were off. We told him we were leaving today and hoping to reach Hayle sometime tomorrow. I outlined the storm damage and briefly told him the plan. It was a little concerning that the small fishing boats were coming back into port but we had double checked the forecasts. He shrugged dismissively about the returning fishing boats. There was one potential problem: Sick Tony.

“The medication seems to work,” Tony grinned.

Yuk! To Be Avoided At All Costs

Nodding a smile at Tony the lifeboatman said they were there if needed and he went on his way. I do like the Penlee people.

The Newlyn, Observer Status, Lifeboat Station and the New Home for the Famous Penlee Lifeboatmen

An Inauspicious Start

The small fishing boat were still coming in as we waited for the tide. I decided we should leave early to give us more time in daylight. One of the returning fishermen helped manhandle the boat around the pontoon end so Newlyn Maid was pointing in the right direction. He seemed puzzled that we didn’t just reverse out. Tony laughed and said

“Don’t encourage Steve in a harbour he’ll only bump into stuff. He can’t even park his car. He’s useless I tell you.”

Steve in Newlyn Harbour

Pulling away from the pontoons I switched on the depth gauge and kept my eye on it. It was still under test. The device had performed well ever since the bizarre readings on the Fal. A Falmouth boat builder said the inaccurate readings were just one of those things; it had probably had been shaken about in the storm. In reality, it was accurate but gave silly readings over shallow rocky bottoms and this would be confirmed in the next couple of minutes.

As started away from the pontoons, the Maid’s junk sail was not supported by its storm damaged gallows and formed a rumpled cloth wall blocking my view. With no visibility over the port side I asked Tony to keep a visual check and give directions as we pulled away so we stayed in the channel. Of course, I should have realised he was proper Cornish and would take a “Madder Dooee” [does it really matter?] attitude. He let me cut the corner which would be fine with a higher tide. The boat touched bottom a few metres outside the channel – in what the depth gauge said was over 10 feet of water again!

I started to ask why he had not bothered with the channel marker. He was supposed to be crew not a passenger.

“It’s a harbour. And its tradition. You looked like you might make it out OK without a problem. I wasn’t having that. We have to respect your dyspraxia. Proper job.” He laughed.

“I haven’t got bloody dyspraxia,” I replied.

“That’s not what I’ve heard. And I am the one who had to teach you how to park your car. You’ve only been driving for 35 years.” He said laughing and winning the argument hands down.

“OK. We’re stuck here for about an hour. Let’s tell the harbour master and have some coffee.”

We switched on Radio 4, opened the coffee, and had some pie. Neither of us normally eat breakfast. It was now mid-afternoon and this was the first food since the day before. We managed a small slice of a pie each. Sitting drinking coffee, we waved to the small fishing boats as they returned. Tony was highly amused and said it’s like we picnic here every day.

All the small fishing boats were coming back in. The fishermen would occasionally call out a warning about the sea state. Were they serious? I couldn’t imagine them all scuttling back into harbour for nothing. Perhaps the weather really was awful. I cautioned Tony that an unsettled sea might well be the case and we might not get far out of harbour before turning back.

Tony had been involved throughout the strengthening and rebuilding of Newlyn Maid. He now looked over at the fishing boats and thought them dangerous. Open boats without extra buoyancy were not ideal in the frequent local storms. One large wave over the top and they could be flooded. Tony had been out in a moderate sea and taken the Maid over reasonable waves and not been sick. Bad weather – Madder Dooee? He was going.

A Pleasant Sail

There was a reasonably strong wind that was not blowing from the forecast direction. Throughout this trip, we would be battling against headwinds. Tony was helmsman as we headed down Mounts Bay and out to sea. His instructions were to get and stay at least a mile out from shore. The further we were away from the rocks the safer we would be. On the helm, Tony was fine not the slightest hint of nausea all the way out of the bay and into rather larger waves than forecast. It is always difficult to estimate but they seemed to have built to about 8-feet and were the typical short nasties that seem to plague Lands End.

Tony was in his element guiding the Maid slowly over the waves. She was moving slowly about 2-3 mph (knots) over the ground. I had set just a couple of panels in the sail for stability in the wind. It was slow but steady progress. She climbed up the face of the waves lingered for a moment and glided down. Tony was fascinated.

“This is great,” he mused. “There’s none of that macho crashing through the waves she just floats gently over them like a cork.”

Tony was at the helm for 5 to 6-hours. We hoped steering the boat would help him avoid the dreaded mal de mer. It was starting to get dark and Tony looked tired. Being at the helm in wind and waves takes it out of you. He had done a good stint.

I suggested taking over the tiller while he had a rest. A few hours sleep and he could take the helm again. He couldn’t get comfortable in the cockpit. Going down in the cabin, he needed to put an extra seasickness tablet next to his gum and slap on a skin patch. The dermal patch was for long-term prevention of seasickness and they take a few hours to start working. Once someone begins to be seasick, it’s normally too late and difficult to reverse. I threw Tony the box of patches and watched him put one on. I also watched him put an anti-sickness tablet next to his gum, to make sure he stayed medicated while waiting for the patch to take effect.

This trip was a real test for Tony. So far he had been perfectly fine – not a hint of nausea. However, going down in the cabin was something else. You get thrown about from one side of the boat to the other by the wave action. There is no warning or even much of a pattern. Unpredictable pitching, rolling, and yawing is enough to make anyone sick. The one time I had felt sick since starting to sail the Maid was in the cabin at anchor. Tony would need to lie down, or hang on tight, and hope the medication worked.

A Dead Chicken Lands

Newlyn Maid was happily sailing under two panels and I conserved energy by stabilising the tiller with a bungee-cord. It became pitch black shortly after Tony went below and the waves continued to increase in size. Just occasionally we passed close to a bamboo pole piercing a crab pot marker. The markers looked different sticking out of the side of waves at odd angles.

Usually, I stayed well away from the markers but it was so dark they could not be seen until they were alongside the boat. The spray built up as the rain and disturbed sea filling the air with a fine mist. While I could make out the navigation lights in the distance, I could see only a few feet ahead. There was a sudden thump up above. The sail shook and something fell onto the cabin floor.

European Storm Petrels – Mother Carey’s Chickens

The bump in the rigging seemed like just another noise in the weather. Later at daybreak, I would realise a black seabird had come to grief. A Storm Petrel had smashed headlong into one of the sail battens and fallen into the cockpit. The bird was stuck by rigor mortis in a soaring position killed instantly in mid-flight with a broken neck.

In the morning light, I would hold the bird up for Tony to identify. He couldn’t recognise it but would look it up when he got home. This failure was not surprising as storm petrels breed in uninhabited areas and usually at night. Petrels spend most of their time sitting on the water out to sea using high winds to help them take flight. The petrels warn sailors of oncoming storms that may reflect the birds flying in high winds.

Mythically, killing a storm petrel portends just about as much bad luck as a Cornish sailor can bring upon himself. Killing one of “Mother Carey’s Chickens” seems to be about as bad as doing in an albatross. The petrels are apparently the souls of sailors drowned at sea. Just across the way in Breton folklore, storm petrels are the spirits of sea-captains who abused their crews and were cursed to spend eternity warning sailors of bad weather. In our blissful ignorance, we did not know the bird, its symbolism, or that we had just destroyed one. For those who believe in luck – this was bad.

Cursed?

Things started to go wrong immediately after the storm petrel hit. The already strong wind picked up even more, as if out of sympathy for the dead bird. The waves became larger and more threatening. The conditions were nowhere near as bad as in my recent Lizard storm but not nice all the same. Despite their size, the waves were well-behaved and not breaking much. These conditions were challenging on the helm but my only concern was that they did not make Tony sick.

We headed into the wind taking the waves at an acute angle. I could not see the oncoming waves and was steering the boat by feel. The waves occasionally threw a little water into the cockpit, not much, just enough to make sure everything was soaked. Rain added to the soaking and I moved all the sensitive electronics into the cabin. I navigated by eye using the hand-held GPS as a direction and speed indicator.

Gradually the boat stopped steering well and I checked the bungee-cord steering. The connection where the bungee was chained to the tiller (a small metal cleat) had come loose. I would now need to steer by hand. The bungee had allowed me short periods of rest. Taking full control of the tiller gave another warning. It had several degrees of additional play. Imagine a car’s steering wheel turning loosely from side to side, about 10 degrees, without changing the car’s direction. I could not see the cause but the rudder had been checked. It seemed likely the movement was at the top of the rudder post connected to the tiller, which is known for cracking on Coromandel’s.

Worryingly, the play in the tiller would gradually get worse through the night. I was now steering blind through some ugly waves as delicately as possible.

Collision!

Then it came. A massive crash. The boat had hit something. The noise came from above, a metallic bang as if someone had just smashed a sledgehammer into the mast. I looked up but could see nothing beyond about three feet. From what I could see the sail was OK. It wasn’t. Then I checked down below. The mast was still ringing like a bell several seconds after the impact. Tony was sitting up wondering what was going on.

“We have hit something. Listen to that. The mast is still shaking.” I stated.

“What have we hit? Rocks?” Tony had his Madder Dooee tone. He was miles out to sea in a squall. The boat had just collided with something making a tremendous noise. Bovvered? Did he look bovvered?

“No, they’re miles away. There’s nothing in the water and the hull looks fine. Let me know if we spring a leak.”

“OK. It’s dry at the moment. Bloody noisy, though!” He complained.

He was referring to the crashing of the waves into the bow. Newlyn Maid’s bow slapped into oncoming water as the boat ran down the back of the previous wave. The wave pounding was far louder than the wind singing in the rigging and the general wave noise. Tony looked out of the cabin window to orient himself with our position and saw the sparse shore lights occasionally in the gaps between the waves.

I checked the computer navigation and it confirmed we were well away from any rocks. There had been nothing obvious in the water. Later we would discover a gouge out of the side of the aluminium mast. Something hard and probably steel had smashed into it. This damage was difficult to understand as whatever hit the mast had smashed into it 4-feet from the edge of the deck and 7-feet to 8-feet above the waterline. It had missed any other part of the boat.

How Did That Happen?

A few weeks later when walking in Sennen, we came across a crab/lobster pot marker with a steel pole rather than the usual bamboo pole. Bamboo pole safe – steel pole not so much. Unfortunately, when I returned to photograph the thing it had gone. I could not find another steel pole marker locally, but had seen this in the background while watching the movie Orca:

Steel Pole Used in Marker Buoy

Our best guess is that we hit the end of a steel pole from a marker swinging at an angle in a wave. This answer could explain how the mast and sail came to be hit so high up without any other damage to the boat. Whatever the explanation, it was fortunate that it hit the mast rather than my head.

Sail Damage

Newlyn Maid slowed noticeably. We had been making good progress in the night at about 4 mph (knots). Now we were suddenly down to less than 2 mph. Not only that we could not sail into the wind as before. Something was wrong with the sail. I could not see the damage and was not going forward before it became light when Tony would take over the tiller. Now the boat was moving too slowly to change direction easily, as there was not enough water speed over the rudder. I switched on the engine and started to motorsail. This was not an improvement. We were trying to run over the waves into a high wind. I decided to push forward using higher engine revs. It would burn fuel but worked.

Tony was moving. Perhaps he was going to come up on deck? No, he was trying to vomit. I poked my head in the hatch and asked if he had put on the anti-sickness patch. Tony said he had but it had fallen off in the night. I told him to stick another one on his arm, put two tablets next to his gum, and get on deck quickly. Madder Dooee? He placed the used patch between his watch and his skin and settled back to rest. He was alright and would be up dreckly. Dreckly was scary: it is Cornish for maybe-soon-maybe-never, a bit like the Spanish Mañana without the urgency. I told him in no uncertain terms to get on deck so we could sort him out. His response suggested he was feeling sorry for himself: Madder Dooee?

By morning, we were well round Lands End and several miles out opposite Sennen Cove. The sea was calming down. I could now assess the situation. The top batten was missing from the sail, which explained why we had been making such slow sailing progress. I had been running under a three-panel “storm sail” through the night and the top two panels were bulging useless against the wind.

I switched off the motor to save fuel and raised the sail. Raising the sail increased our speed back to 4 mph (knots) and we could steer into the wind a little more. The sail wasn’t working efficiently but we were making good progress. This speed lasted a couple of hours while Tony was becoming increasingly sick. He would not come out of the cabin despite my urging. There was no refusal to climb out just he would do it dreckly. I would make maximum speed and try to make St Ives Bay with the tide.

Cold

I was now extremely cold. Before setting off, I had put on a layer of thermal underwear under a flotation suit. The temperature dropped with the evening sun and the increasing wind. As the night progressed, I became increasingly soaked. There were more thermals ready for use just inside the cabin. However, letting go of the tiller would have the boat bounce around in the horrible waves. By dawn, I had been cold and wet for hours. Sitting stationary, I was now in the early stage of exposure. I stayed at the helm shivering until there was little choice. If Tony would not get out of the cabin and help, he would have to deal with the boat’s movement as I let go of the tiller. Gingerly I climbed into the cabin to get some extra clothes on as quickly as possible.

Tony had made a little nest for himself on the starboard side. The port side was filled with items for a long sea journey. I threw some bottles of water out on the cockpit floor to keep me hydrated. Tony was surrounded with bottles of water so at least he was not going to become dehydrated. There was no food visible. I knew there was perhaps a months worth of grub packed away but could not get at it without further disturbing Tony. The small slice of pie I had yesterday would last me. The remainder of the pies were now a soggy mess on the cockpit floor. Fasting was fine. I looked about. Anything that could move had been thrown about in the night.

Tony had grabbed what he needed when he felt sickness coming on. Many of these items had been tossed around the cabin in the waves. The shelves surrounding the cabin that had been packed with socks and other items were now mostly empty. At least Tony had been careful to be sick into a large green soft rubber bucket that he held onto like a comfort blanket. Poor Newlyn Maid had bounced about last night. Still I quickly found the spare clothes and climbed back out with two sets of dry thermals under the flotation suit. As the day wore on I would now be boiling hot but it was better than being cold.

More Sail Problems

When I returned to the tiller, the Maid was pointing towards the land. I took my time and pulled her back on course. Then I gave the shore crew an update email that automatically gave the GPS position, speed, and direction. A few minutes later the shore crew phoned. Why was I heading out to sea? Why was the journey taking so long? Why were we so far from land? I told them about Tony being sick, the bad weather, and that it was difficult to keep the boat on course when typing emails to them. They should phone for updates as I could still steer the boat and use a standard mobile. I would phone or email if there were a real problem.

Then the sail collapsed. High wind and buffeting in the night dislodged the sheets (main rope controlling the junk sail). The blocks hit me in the back one after the other. I dropped the sail and went below for some paracord to reconnect the blocks to the hull. One strand of this “shoelace” would nominally take a load of 550 lbs. Tony was throwing up again. I was cursing that stupid St Ives lifeboat, muttering under my breath: “You can’t set the sail up. There’s no wind.” I grabbed a length of paracord went up and created a jury rig. I raised the sail a little but thought better of trying to raise it more. I would get some of the stronger 750 lbs paracord when I next went into the cabin, or if a miracle happened and Tony were to grace the cockpit with his presence. I would add a couple of loops of the 750 paracord to the fastening before raising the sail fully.

Making Repairs?

The damage to the sail and rigging would take about an hour to fix but that would mean an hour of torture for Tony. Tony had become seasick during his first trip on the boat within a minute of letting go of the tiller in a slight sea. He threw up when I got some extra thermals. With no-one on the helm, Newlyn Maid would roll, yaw, and pitch about in a style guaranteed to make Tony’s sickness a whole lot worse.

I could have given Tony a chance to come into the cockpit and take the helm, so I could the repairs. Whatever he decided. This choice would have allowed me to get him into a harbour on the next tide. He would not leave the cabin! Instead, I chose to minimise Tony’s stress, going with the jury rig and a steady boat for the time being. Nonetheless, my being compassionate at this stage was a calculated risk that didn’t work out. There was a good chance Tony would recover as his sickness faded during the day, particularly if he came into the cockpit and took the helm. But there would be no such luck on this trip.

Back and Forth

Gurnard’s Head Looks Quite Different from the Sea

We had gone most of the way under the jury-rigged sail to approximately opposite Gurnard’s Head. Gurnard’s Head is supposed to look like the head of a fish from the sea. I saw the strange face like rock formation and asked Tony if that was Gurnard’s head.

He said a definite “No!” As if I were a total idiot.

I’m still not sure if he were looking at some other section of the coast or if he was being deliberately contrary. It was in the right section of coastline, and certainly looked like the head of a Gurnard to me. But Tony was a real local and should know. In retrospect, I think he was teasing me again. He was getting progressively sicker but still retained his silly humour.

High winds and strong tidal currents meant at times we were travelling in the general direction of Hayle and at other times slipping backwards towards Lands End. I watched as Gurnard’s Head faded into the distance. We were gradually going slowly backwards even though I was sailing as quickly as I dared without fixing the sail properly. Sailing alone I would just have just got on and done the repairs. But Tony was getting sicker. Bouncing around while I made repairs was now out of the question.

Sicker and Sicker

Tony was getting sicker faster than the waves were getting calmer. He needed to stay medicated, take fluids, and get on deck. His Madder Dooee attitude was fading fast. His dreckly coming on deck was becoming more urgent: he gave the impression he might climb out of the cabin in about a fortnight. For Tony, this sounded almost proactive – well nearly. I checked him over looking into the cabin while holding the tiller steady.

We had missed the tide at Hayle so it would be another 12-hours or so before we could get into the harbour. I decided to burn some more fuel to stop backsliding back towards Lands End. Going back to Newlyn was an option but it was now much further than carrying on to Hayle. We could anchor off Carbis Bay or pull into St Ives Harbour. Anchoring would not help Tony’s condition, so St Ives was the best option.

We tracked up the side of the traffic separation zone with the motor revving slowly. It was about as close as we could motorsail to the direction we needed to go without pushing the engine and using excessive fuel. I switched back to sailing as soon as the tide allowed.

As the day wore on we were closing on St Ives Bay but increasingly distant from the land. I needed to try to make harbour on the next tide, or take my time and catch the following tide. The safest thing to do was to take time, work the tide, and sail into St Ives Bay. Could Tony hold on? I asked how he felt, if he could hang on for another day, or should we try for the next tide. Tony felt “awful” but said he could hold on. This guy was brave, and far too tough (or perhaps stupid) for his own good.

My concern for Tony was increasing. I decided to take the risk and motorsail into the bay. We had used a lot of fuel fighting the wind, waves, and tide. I checked the long-range fuel tank and topped it up with the remainder of the reserve fuel. Calculating the amount of fuel and distance indicated we should be OK. I would head inland and cut the corner into the bay. This path would not have been my first choice. We would be going near the land in the tidal race, and hoping the engine stayed healthy. In the unlikely event of engine failure, we only had the lashed up sail to get us out of trouble. Tony would have to let me do the running repairs. There were oars but inefficient rowing was hardly appealing. Reassuringly, the engine was nearly new and reliable.

The Engine Fails

I switched on the motor increased the revs and we motor-sailed in towards the land. The sea was now quite calm. Everything was fine and going to plan. Getting nearer to land the motor just stopped and would not restart. I checked the motor and fuel line and waited a few minutes to let the engine settle. Then after numerous tries it restarted. This should not be happening. Tony was sitting up and vomiting again with the disturbance to the boat’s motion.

We had enough fuel but I was now unsure of the motor. Being close to the North Penwith coast with engine failure did not appeal. The wind was out to sea but could swing round. The sail was a mess. The rudder controls were wobbly and I had been working the tiller gently now since for approaching 24 hours through some bad weather without a break or food. I had only a few hours sleep the night before yesterday. The wind was blustery but the sea remarkably calm as we neared land.

Then the motor stopped again. It restarted after a struggle and we carried on. Perhaps another five minutes passed before the engine stopped yet again, was restarted for a few minutes, and then died completely. The fuel line had a blockage but this was not immediately clear or resolved by removing it and reattaching.

Options

We were only a few miles away from St Ives and about half a mile from the cliffs. We would have been in St Ives in a little over an hour – if the engine were working. There were now three clear options.

- We could use the jury rig and sail. I would need to use the wind, get back out to sea, and come round in a wide arc to St Ives Bay. Or I might sail with the wind to the Scilly Isles. Both destinations would mean another day at sea.

- I could drop the anchor and sort the boat out. This would probably make Tony sicker. Then he would need to suffer another 12-hours before we could get into the harbour. This was my preference.

- We could get the shore crew to arrange for one of the local working boats to come and give us a tow into St Ives. We knew several of the local fisherman and sailors. The weather was now calm and the fishermen could use the money they would receive for the tow. It would mean a tow rather than transferring Tony onto the fishing boat since there was no way we would be able to get Tony out of his little den formerly known as the cabin.

Tony Gives Up

I told Tony the engine was failing and we still had a problem with the sail; it would be at least overnight and probably a whole day before we could make a harbour. How was he? Could he make it? He needed to get out of the cabin and onto the tiller while I fixed the boat. This was no longer a request. He needed to get out of the cabin.

Tony sat up then threw up and said, “I can’t feel my hands or feet. I think I might die!”

This was confusing and not a common symptom of sea-sickness or mild dehydration. Later I would realise he had been lying on a hard foam surface and bracing himself against the waves. The result was pressure on his peripheral nerves. When sleeping on the boat, I had experienced “dead hands” from pressure at the shoulders and elbows. I did not put two and two together and was now, even more, concerned for him.

He tried standing – well crouching up against the roof in the tiny cabin.

“I can stand. I have no balance at all.” He fell back down.

“How long can you last?” I enquired.

“Not long. I think we need a tow.” He replied and threw up again.

I hadn’t given him that option but he said he needed help. I told him to stay hydrated. He nodded. Tony’s attitude was no longer Madder Dooee.

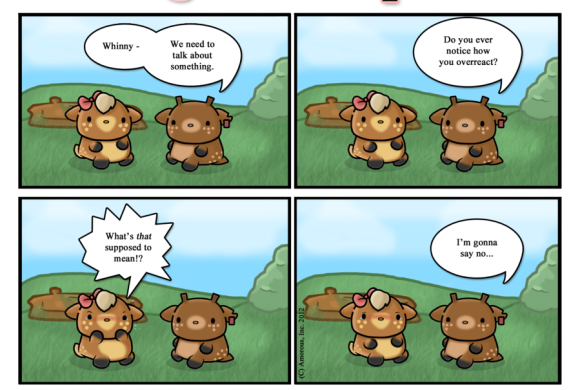

Sick Tony?